The Marchutz Tapes — Reflections on Art

Sacrifice, So Dear to Delacroix

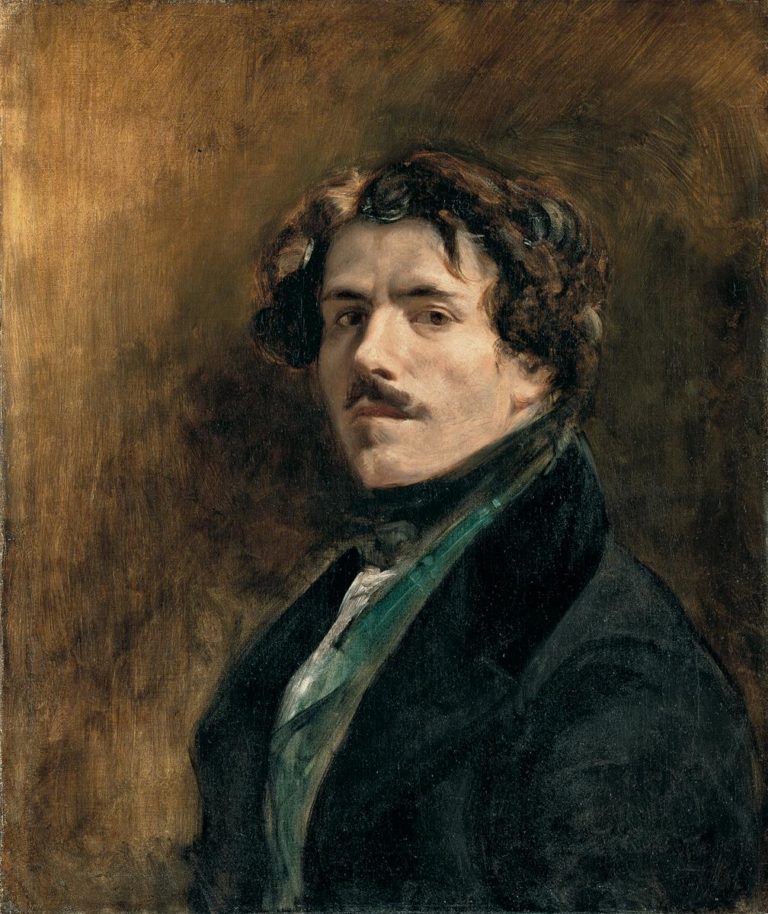

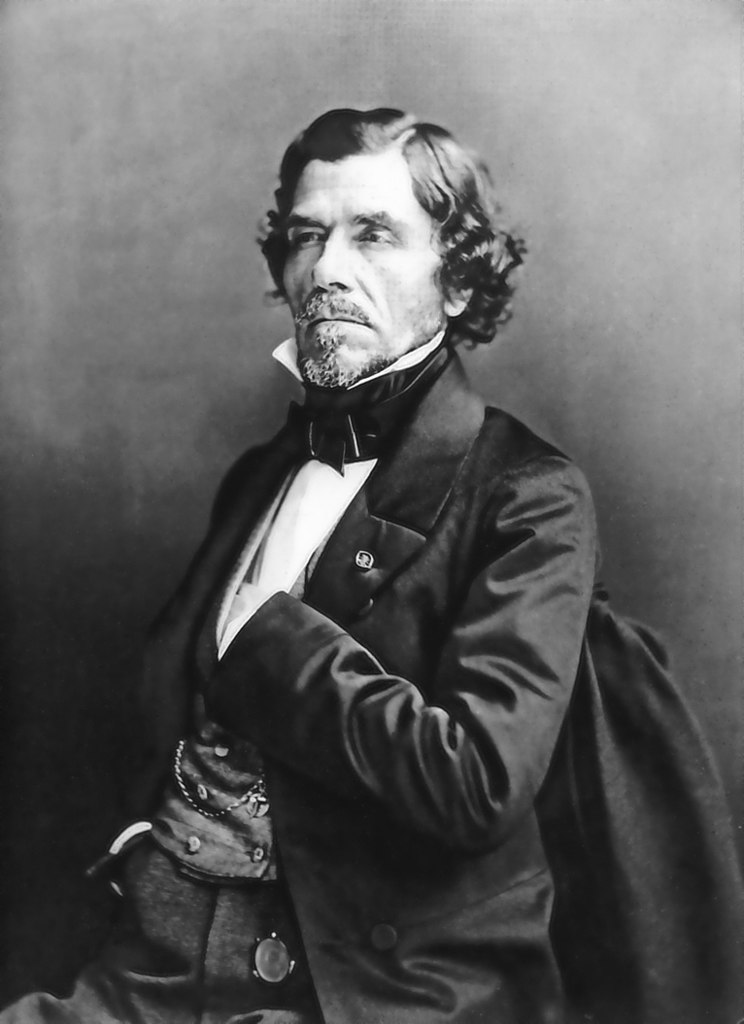

In his article « From Nuremberg to Aix-en-Provence » published in the monograph of Leo Marchutz, Albert Chatelet quotes on several occasions Eugene Delacroix and more specifically his notion of sacrifice.

As a contribution to this discussion, to which Leo alluded several times in The Tapes, I think it important to quote the translation of Eugene Delacroix’s Journal entry, dated April 23, 1854 in which he exhaustively writes on this subject:

The first idea, the sketch – the egg or embryo of the idea, so to speak – is nearly always far from complete; everything is there, if you like, but this everything has to be released, which simply means joining up the various parts. The precise quality that renders the sketch the highest expression of the idea is not the suppression of details, but their subordination to the great sweeping lines that come before everything else in making the impression. The greatest difficulty therefore, when it comes to tackling the picture, is this subordination of details which, nevertheless, make up the composition and are the very warp and weft of the picture itself.

If I am not mistaken, even the greatest artists have had tremendous struggles in overcoming this, the most serious difficulty of all. Here, it becomes even more obvious that the disadvantages of giving too much interest by grace of charm in execution is that at a larger stage you bitterly regret having to sacrifice them when they spoil the whole effort. This is where the specialists in light and witty touches, those people who go in for expressive heads and brilliant torsos, meet with defeat where they are accustomed to triumph.

A picture built up bit by bit with pieces of patchwork, each separate piece carefully finished and neatly placed beside the rest, will look like a masterpiece and the very height of skill as long as it is unfinished : as long, that is to say, as the ground is not covered, for to painters who complete every detail as they place it on the canvas, finishing means covering the whole of that canvas. As you watch a work of this type proceeding so smoothly, and these details that seem all the more interesting because you have nothing else to admire, you involuntarily feel a rather empty astonishment, but when the last touch has been added, when the architect of this agglomeration of separate details has placed the topmost pinnacle of his motley edifice in position and has said his final word, you see nothing but blanks or overcrowding, an assemblage without order of any kind. The interest given to each separate object is lost in the general confusion, and an execution that seemed precise and suitable becomes dryness itself because of the total absence of sacrifices. Can we expect from this almost accidental putting together of details that have no essential connection, that swift keen impression, that original sketch giving the impression of an ideal, which the artist is supposed to have glimpsed or fixed in the first moment of his inspiration?

With the great masters, the sketch is no dream or remote vision ; it is something much more than a collection of scarcely distinguishable outlines ; great artists alone are clear about what they set out to do, and what is so hard for them is to keep to the first pure expression throughout the execution of the work, whether this be prolonged or rapid. Can a mediocre artist, wholly occupied with questions of technique, ever achieve the result by means of a highly skillful handling of details which obscure the idea instead of bringing it to light? It is unbelievable how vague the majority of artists are about the elementary rules of composition. Why indeed should they worry over the problem of retaining through their execution an idea which they never even possessed?

Eugene Delacroix,

Excerpt from his journal, dated April 23, 1854. Translated by Lucy Norton.

A few years later, in January 10, 1857, Delacroix was elected to the Academie. In the following days he began to write his Dictionnaire des Beaux-Arts; on January 13, 1857 under the word interest and then later under sacrifice, Delacroix writes:

Interest: The art of concentrating the interest on essential points. One must not show everything. This seems difficult in painting, where the mind is only able to imagine what the eye perceives. A poet does not find it hard to sacrifice minor issues or to pass over them in silence. The art of the painter consists in drawing attention only to what is essential, yet at the same time …. (unfinished sentence in the original)

Sacrifice: What must be sacrificed, a great art unknown to beginners. They want to show everything.

You may also find allusions to the theme of sacrifice in following dates of Delacroix’s Journal:

– July 10, 1847

– Brussels, Tuesday, July 9, 1850

– Wednesday, April 20, 1853

– Thursday morning, April 22, 1853

– Wednesday, October 12, 1853

Painter, poet, and musician, Tristan L. Klingsor (1874 – 1966) writes in his book about Cézanne, released in 1923:

« He [Cézanne] looks for the big masses, the big shadows, the big accents, and it is by this means, and not through detail, that he reaches the intensity of expression. In this sense, the portraits of his father, his self-portraits, those of Choquet are the most conclusive ones. »

It seems that the opposition between mass and outline, initiated by Delacroix as a fundamental principle of painting, was a common issue for the painters of the next generation and it remained so until the beginning of WW. II. It is, as Klingsor states, very much applicable to the artwork of Cézanne.

Excerpt chosen by

Antony Marschutz

Since he retired in 2008 from his activity as a musician, Antony Marschutz dedicated a great deal of his time to promote the work and the thinking of his father, the painter and lithographer Leo Marchutz. He released several books containing documents left by Leo Marchutz concerning his life; the life of his family, compelled to emigrate to the United States; as well as his opinions on art and art history contained in his journals and correspondence. He also participates in the organization of exhibitions in France and Germany.