The Marchutz Tapes — Reflections on Art

Form and The Imagination of the Artist: Hands

I have always been astonished by the hands in the work of Leo Marchutz. How did he conceive of such abstractions that are so pertinent to the form of the whole painting or drawing? Marchutz addresses this in the tapes.

TO COME BACK TO THE NEW FORMS we talked about. That is of course a very difficult thing, because form concerns, like volume, the whole painting. And when there are, well, different renderings let us say, or figures, or where the accents might lay on elements which have…. where they did not repose before or lay before, well then one can say there are new forms in creation, conditions of the whole work. There are a hundred ways or a thousand ways of rendering hands. One can even say that each artist, if he renders hands, does it in a different way. If there is cohesion, and something different from what has been done before, then one can say there are other forms being created.

For instance hands in the work of Kokoschka, one should say, looking at his beginnings, that there is something coming, something different, something new. But it peters out. His later works, concerning hands, it was horrible, they conform. Whereas in the beginning there is an attempt to make the hands render something which has never been rendered.

And so, concerning art in general, I think I am absolutely right, if I pretend que in painting, everywhere hidden treasures can be found. They lay on the road, and we have only to find them, to see them. It is stupid to think that there are no more possibilities. For instance, in portrait painting there is everything still possible. But it is difficult, because everybody is aware of what has been done before and it is very difficult to free oneself from these influences and to have an unprejudiced view on people and things.

Leo Marchutz,

Excerpt from The Marchutz Tapes, 1974-1976

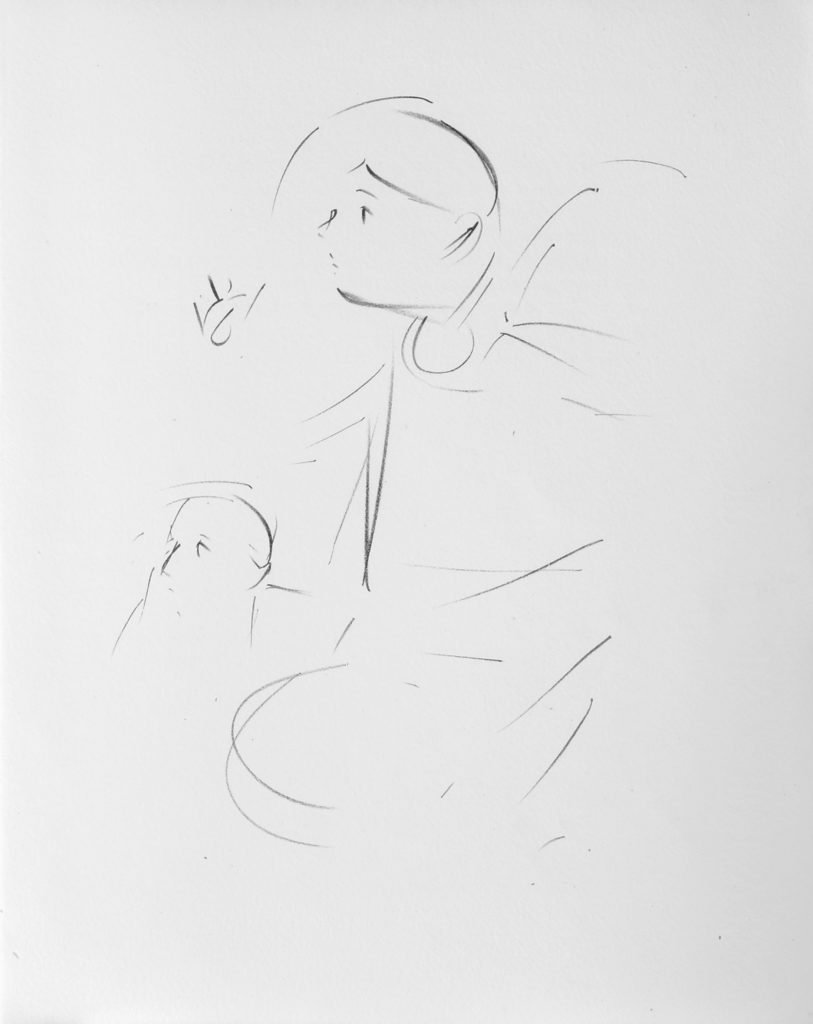

If we speak of paradox concerning Leo Marchutz, we must stop to examine an image from his St Luke..But first consider the craft. We have seen the artist abandon oil paints in his efforts to save the purity and spontaneity of his first impression. Materials, the pigment, the crayon were always subservient to his sparse images. Ironically, however, lithography, a complicated process with its rollers, ink presses, stones, and other cumbersome equipment, freed the artist to express himself in a pure, essentialist style. Gabriel, leaves no hint of the complexity of the craft involved behind the image. It appears to have been breathed onto the page. As Venturi notes in the book’s introduction, “the images created by the artist appear on these pages as if delivered to the atmosphere on a wind which long ago would have been called ‘astonishment.'” Astonishment at what?

“And there appeared unto him an angel of the Lord standing on the right side of the altar of incense. And when Zacharias saw him, he was troubled and afraid. But the angel said unto him, Fear not, Zacharias, for thy prayer is heard; and thy wife Elisabeth shall bear thee a son, and thou shalt call his name John . . . I am Gabriel, that stand in the presence of God; and am sent to speak unto thee, and to show thee these glad tidings. And behold, thou shalt be dumb and not able to speak, until the day that these things shall be performed because thou believest not my words, which shall be fullfilled in their season.”

Marchutz did not illustrate the text; in fact, here illustration is the antithesis of his expression. Marcel Ruff insists that “meditation” is the better descriptive noun for these works. Marchutz, as an artist, had contemplated the Gospels for many years. The image is not a historical account but an attempt to render, through the barest of essentials, the imminent possibility of the miracle and its ramifications. The angel, larger than life with an absolutely clear gaze and untroubled conscience, messenger of God, announces that which is certainly impossible. But he announces not through words but through a symbol–the hand. “Marchutz is not afraid to detach a hand from the body when it is necessary for the hand to speak,” says Venturi .” (Or, as Delacroix stated, “the important thing is not so much the finish of a foot or hand, as the expression of a figure through movement. . . a hand indeed–but a hand must speak like a face.”) Gabriel’s hand speaks: it announces. Six or seven abstract strokes of extremely nuanced value, the angel’s hand is a symbol of God’s decision. Visually it works as a transitional element between the angel and Zacharias. Zacharias, in his disbelief, is frightened. Rather than concerning himself with his destiny, he looks to the exterior and the awaiting crowd. With his refusal to recognize his fate, he is thus struck dumb — a universal image in life and myth.

Excerpt from the essay “An Affirmative No”, Alan Roberts

Excerpt chosen by

Alan Roberts

Painter